The Battle Of Luzon, Part 1: Climax Of The Southwest Pacific War

Inside the imperial palace in Tokyo, Prime Minister Koiso Kuniaki stood uneasily before his Emperor Hirohito and apologized for the catastrophe that had just befallen his majesty’s army and navy at the hands of the Americans on and around the Philippine island of Leyte. In the fierce land and sea combat that lasted from October 17 to December 24, 1944, the backbone of the Japanese fleet, as well as some 65,000 troops and hundreds of aircraft, were erased from the order of battle. When the Emperor reminded Koiso that he’d promised Leyte would be a repeat of Japan’s 1582 victory at Tennozan, the prime minister sheepishly mumbled that Luzon, not Leyte, would be the Kentai Kessen, “decisive battle,” that would once and for all destroy the Americans and their allies advancing ever closer to the home islands.

Luzon was the main island in the Philippines archipelago, and site of the nation’s capital city Manila. Slightly larger than Cuba, it stretches some 460 miles running north-to-south, and sits roughly equidistant between Japan and Australia. If Japan could not fight off the Americans here and regain the initiative then the sea lanes between the home islands and her vital raw materials in the Dutch East Indies, which had been severed when Leyte was lost, would be forever cut off. And should Luzon fall, only the island bastions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa stood between the Allies and Japan.

General Douglas MacArthur and Philippine president Sergio Osmena in a landing craft on their way to ceremonies proclaiming the liberation of Leyte, 23 October 1944. National Archives. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Bearing down on Luzon was an immense U.S. invasion force of over 800 ships, 3,000 landing craft — many just arrived from Normandy — and some 280,000 troops. This formidable army, fielding more men than Eisenhower landed at Sicily, was led by America’s most brilliant strategist, Five-Star General Douglas MacArthur. For two years this American Caesar had dazzled the Japanese with one victory upon the next in a relentless drive up New Guinea and the Bismarck Sea with the aim of recapturing the Philippines.

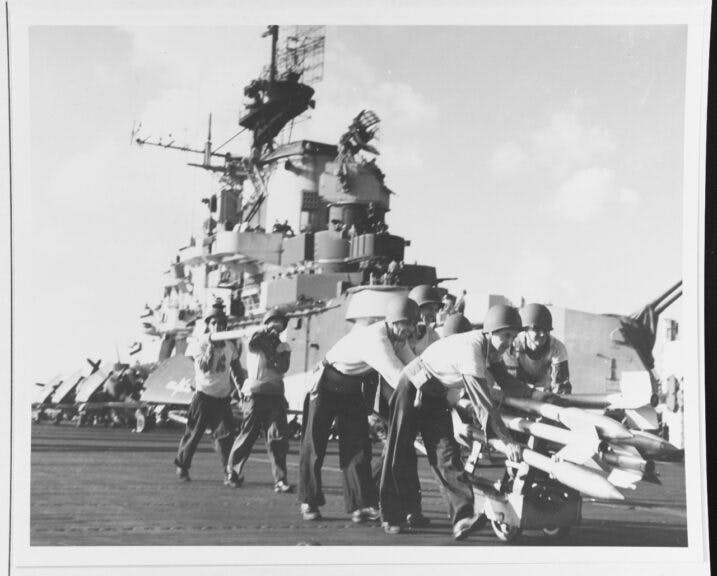

Carrier Raids on Formosa, October 1944. Crewmen on USS Hancock (CV-19). National Archives. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Beginning in November 1942 with a grinding, bloody fight for Buna on New Guinea’s northern coast, MacArthur’s advances steadily accelerated. Utilizing amphibious thrusts by coordinating land, sea, and air power — what Churchill described as “triphibious warfare” — the general leapfrogged from beachhead to beachhead in ever more audacious envelopments up the world’s second largest island. Indeed, by the time his landing force steamed towards Leyte in October 1944, the first of the Philippine islands targeted for assault, MacArthur had captured more territory while suffering fewer casualties than any commander in modern warfare — while inflicting ten times as many losses on the enemy.

MacArthur now set his determined sights on the ultimate prize, Luzon, 300 miles north of Leyte. Waiting for him, however, was a Japanese garrison numbering some 270,000 determined troops, the largest enemy contingent the Americans would confront in the Pacific War. Moreover, the Emperor’s forces would be under the overall command of a formidable general in his own right, Tomoyuki Yamashita, the “Tiger of Malaya.” On this most vital Philippine island, two gifted generals, each at the height of his power, would face off in the climactic battle of the Southwest Pacific campaign.

Japanese army general Tomoyuki Yamashita. US Army/Getty Images.

Although the primary aim of seizing Leyte in the fall of 1944 was to provide MacArthur an aerodrome from which Allied planes could cover his Luzon campaign, as well as stage raids on Formosa and the Chinese mainland, the soil proved to be unstable during the rainy season, which had just begun (24 inches of rain fell in November alone). Although some air bases were eventually operational, due to the soggy runways as well as washed out roads in need of constant repair, MacArthur’s air chief, General George Kenney, was unable to utilize the bulk of the island’s airstrips for the upcoming operations. Still, even with this unexpected setback, the imaginative MacArthur saw an opportunity.

The island of Mindoro, a mere hour-and-a-half ferry ride from Luzon and just 200 miles from Manila, offered ideal ground for Kenney’s aircraft. Adm. Chester Nimitz, MacArthur’s naval counterpart, agreed to support an operation to seize the island, with Adm. William “Bull” Halsey’s carrier task force providing vital top cover until Mindoro could be seized and converted into a land-based aerodrome. But the approach was dangerous. So perilous, in fact, that MacArthur’s reliable naval head, Adm. Thomas Kinkaid, vehemently opposed the landings as he feared his transports would be exposed to attacks from land-based enemy aircraft — especially the deadly Kamikaze suicide planes that made their debut at Leyte and whose attacks were growing in number and lethality — as the vulnerable convoy wiggled its way through the narrow waters of the Surigao Strait and Sulu Sea. Furthermore, should there be a significant number of Japanese on Mindoro, the operation could be costly, even repulsed. The Joint Chiefs in Washington, DC were also alarmed; the Pentagon declared MacArthur’s plan “too daring in scope, too risky in execution.”

But MacArthur’s sixth sense told him Yamashita had no stomach for another Leyte, but was instead husbanding his strength for the defense of Luzon. He also might have assumed that, just as his subordinates had been frightened by the hazards facing any convoy on the narrow approach to Mindoro, Yamashita would figure no enemy would risk such a passage. MacArthur’s contrarian instincts proved correct.

Mindoro Operation, December 1944. Photographed from USS KADASHAN BAY (CVE-76). National Archives. Naval History and Heritage Command.

On December 16, 1944, 10,000 American troops raced from their Higgins boats and overwhelmed the barely 1,000 Japanese stationed on Mindoro; the GIs soon captured four abandoned airstrips. The U.S. suffered just 240 KIA (a mere 18 on the ground, the rest Naval losses from air attacks). And unlike Leyte, the ground here was solid. U.S. engineers went to work refurbishing the captured airfields and constructing two more. Overhead, Halsey’s pilots fended off waves of marauding Japanese fighters and suicide planes swooping down from Luzon. By New Years Day 1945, an ebullient Kenney declared Mindoro his main aerodrome, allowing MacArthur to once again operate under the protection of his land-based air force.

The capture of Mindoro, the last stepping stone to Luzon, also confronted Yamashita with the possibility that MacArthur could hit him from the south as well as the obvious landing spot in Lingayen Gulf 140 miles north of Manila. And he was now cut off from his garrisons in the southern Philippines.

acprints. Getty Images.

Yamashita’s motivations for defending the island were purely military. But for MacArthur, his return to the Philippines was a deeply personal crusade. He’d lived in the archipelago for many years and felt the U.S. had a solemn obligation to free a people over whom we’d assumed responsibility after wresting the islands from the Spanish in 1898. He had been in command of the joint US-Philippine army in December 1941 when the Japanese invaded. Abandoning the capital, he consolidated his forces on the Bataan Peninsula due west across Manila Bay, and the Island fortress of Corregidor covering the mouth of the inlet. The General had hoped to fight a holding action, anticipating a U.S. relief force would come to the rescue and save his command.

In early 1942, however, Japan was at the zenith of its power while the U.S. was just getting on a war footing, and thus in no position to relieve the beleaguered defenders. In May 1942 a combined 75,000 ragged and malnourished American and Filipino troops surrendered. Although it had been a heroic if forlorn stand that upset the Japanese timetable, it was the largest capitulation of U.S. forces in history.

May 1943: Premier Tojo arriving in Manila. Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

MacArthur believed his government had abandoned not just the brave garrison, but also the 18 million inhabitants of his beloved islands to a cruel occupier in the dark days of the war’s opening rampage of Japanese conquest following Pearl Harbor. He also felt an individual obligation to return as he’d been ordered by FDR to leave his doomed garrison and escape to Australia before the inevitable defeat, where he would organize the island continent’s defenses and then lead the eventual Allied counter-offensive in the Southwest Pacific. For almost three years, while American and Filipino captives languished in brutal captivity* and civilians endured privations and repressions, the Japanese military ruled the American protectorate.

JOIN THE MOVEMENT IN ’25 WITH 25% OFF DAILYWIRE+ ANNUAL MEMBERSHIPS WITH CODE DW25

But now, to the jubilation of the Filipinos, who’d feared their islands would be bypassed in favor of a U.S. landing on Formosa farther to the north, and thus abandoned a second time, the Americans were back.

Carlos Romulo, the Philippine writer and diplomat who had been with MacArthur on Corregidor, was one of the General’s confidants. When in October he descended from the transport John Land to join the landing party of brass, politicians and war correspondents onto the barge headed for the beaches of Leyte, MacArthur embraced his friend. “Carlos, my boy, how does it feel to be home?” Two months later, the elated Romulo found himself in Lingayen Gulf amidst a vast Allied armada whose ships stretched out to the horizon. Thirty-seven agonizing months before, it had been a Japanese landing force in these waters. He recalled his “cold horror” when Manila Radio announced the news of Japanese transports in Lingayen. But now, he wrote with satisfaction, “it is their turn to quake.”

Meanwhile, following an interview with Yamashita who promised, “I shall write a brilliant history of The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere on the Philippine Islands”, Radio Tokyo confidently announced: “The battle for Luzon, in which 300,000 American officers and men are doomed to die, is about to begin.”

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities fund manager, author, and columnist whose articles have appeared on the pages Daily Wire, The Wall Street Journal, NY Post, NY Daily News, National Review, The Hill, The Federalist, Zerohedge and other outlets. He is the author of three books. Follow him on Substack and X/Twitter.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Daily Wire.

* * *

NOTES:

- In World War II some 40% of U.S. POWs died at the hands of the Japanese, as opposed to only 1% of those captured by the Germans.