‘History will judge me’: The untold story of India’s quiet transformer

Former Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh died in New Delhi at the age of 92

India’s 13th prime minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh, who passed away on Thursday night after losing consciousness at his home in New Delhi, will be noted as one of the most historically significant people to lead his country. He opened up the economy, gained America’s confidence in India in the post-Cold War 21st century, pushed through a host of social legislation, and laid the groundwork for digitization of the economy.

He did all this while remaining low-profile, so much so that the political opposition, led by his successor, the then Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi, called him a “weak” prime minister. (It did not help that his former media advisor wrote an account of his first term, 2004-2009, and called him an “accidental prime minister.”)

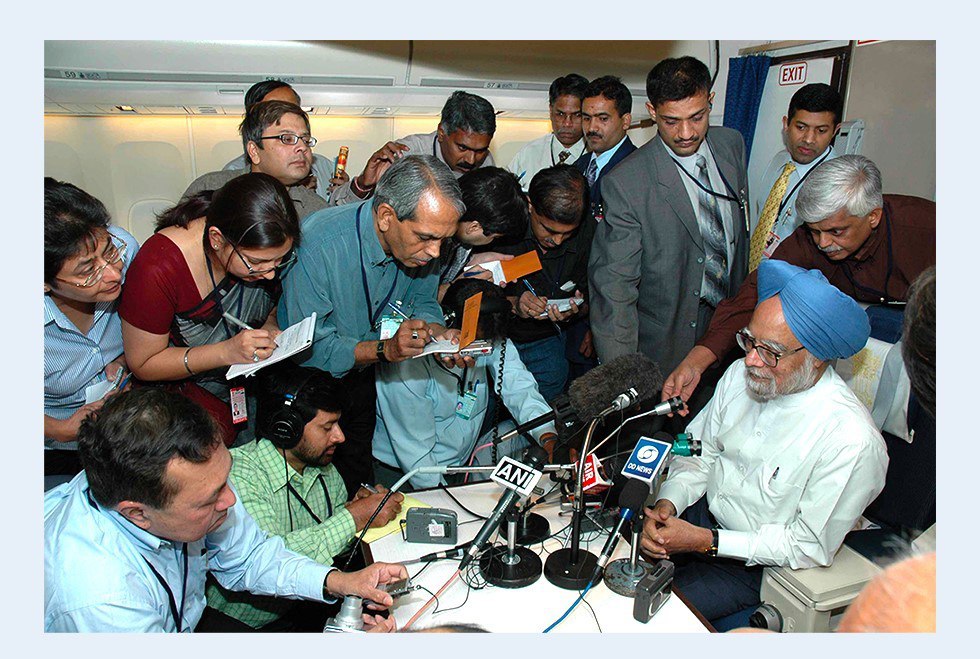

To this, at his last press conference in early 2014, he said two things: “History will judge me kinder than the contemporary media,” and “if you mean by strong, someone who commits mass massacre of innocents in the streets of Ahmedabad then that’s not strength”; the latter was a reference to the 2002 Gujarat riots when Modi headed the state.

Manmohan Singh was certainly India’s most educated leader, even more so than the first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, though Nehru spent time in prison and wrote many popular books. This achievement is all the more admirable given that he was born in a village in what is now Pakistan and had to study under a lamp, a fact that he later attributed his weak eyesight to. His academic journey went via Amritsar and Cambridge, where he studied economics, to Oxford, where he earned a doctorate.

He was working for the United Nations when he was called back to India and thus began a series of official appointments, including the chief economic advisor, governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the country’s central bank, and then the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission.

Ironically, while Singh helmed the RBI, Pranab Mukherjee, who served as the 13th president of India from 2012 until 2017, was Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s last finance minister – before her assassination in October 1984.

Thus, for two years, Mukherjee was Singh’s administrative boss; the roles were reversed two decades later when Mukherjee became Singh’s defense minister, and later finance minister.

© Sonu Mehta/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Another twist of fate came when the former prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi, was assassinated by a Sri Lankan terrorist group, in 1991. Rajiv had publicly referred to the Planning Commission, while Singh headed it (the chairman is an ex-officio post, held by the president of India), as a “bunch of jokers.” Singh nearly quit to return to academic life, but amends were made.

Rajiv had been in the middle of campaigning for the 1991 parliamentary election, and the wave of sympathy generated by his assassination brought the grand old Indian National Congress party, to which both Rajiv Gandhi and Manmohan Singh belonged, back to power (after being in opposition since November 1989).

PV Narasimha Rao, who had packed his belongings to live in retirement in his native Andhra Pradesh state, was selected to lead the party. Seeing the world change as the Cold War drew to a close, he felt India needed a new economic direction and tapped the director of the London School of Economics, IG Patel, who was Singh’s predecessor at the RBI. Patel did not want the job.

Just three months earlier Singh, in an interview to the Financial Express’s Sanjaya Baru (who later became his media advisor), said that India needed to open its economy, pointing to the success story of South Korea.

Patel recommended him, and Rao appointed him as his finance minister.

India’s finances had been in a precarious state due to large deficits run up by Rajiv Gandhi, who modernized the army with large-scale defense purchases, and who introduced computerization to the country, starting with its sprawling railways network. Due to a balance of payments crisis, Rao’s predecessor as prime minister, Chandra Shekhar, had to mortgage gold to the Bank of England for a World Bank-IMF loan.

© PIB

This added urgency to Singh’s determination to liberalize the economy, which he did by abolishing the “license raj” (a period of significant government intervention in India’s economy, marked by bureaucratic red tape) in his first budget. He also introduced a new industrial policy, simplifying the red tape, and oversaw a 10% devaluation of the rupee twice in one week. GDP growth soared to 9%, far beyond the traditional 2% “hindu rate of growth,” as economists used to call it.

This was enough to cement his place in history, but it did not win him popularity, for the Indian left was still strong despite the collapse of the USSR, and Singh could not even win the only parliamentary election he contested, from the urban south Delhi constituency in 1999.

Subsequently, he remained a Rajya Sabha (Parliament’s upper house) member from Assam, even after he became prime minister in 2004.

When the Congress party-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) unexpectedly won the 2004 parliamentary election, members of the outgoing government led by Atal Behari Vajpayee did not expect to be handing the reins over to Singh. “We thought Sonia Gandhi was going to be the prime minister,” former spy chief AS Dulat said, referring to Rajiv Gandhi’s widow, who was now the Congress party president. When Dulat handed his resignation to the new prime minister, it was returned. “Stay,” Singh said. (He did not.)

© Ajay Aggarwal/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Singh began work on two fronts: the US and Pakistan. Unfortunately, his national security advisor, JN Dixit, a former foreign secretary and a former ambassador to Pakistan, died after just eight months on the job. He was succeeded by an intelligence chief who managed to help steer a nuclear deal with Washington – despite opposition from the left, which was supporting the UPA government – and accelerated the growing closeness of the two democracies.

Despite finding a willing partner in Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf, with whom a four-point deal on Kashmir was almost finalized in 2006-2007, the forward movement did not materialize. Musharraf was deposed, and a year later, a horrific terrorist attack on Mumbai in November 2008 pushed peace beyond anyone’s political capability.

In the end, Singh faced too much bureaucratic resistance to his peace efforts with Pakistan. (He did try after being re-elected in 2009, with a meeting with Prime Minister Gilani in the Egyptian resort of Sharm-el Shaikh, but it was vetoed by “the party”, i.e., Sonia Gandhi.)

The UPA’s re-election in 2009 can be attributed to the Singh government’s waiver of 600 billion rupees ($12.66 billion at the prevailing exchange rate) in farm loans. His government also passed legislation on the right to information, right to education, and the welfare Rural Employment Guarantee plan, wherein the unemployed could get 100 days of paid labor. He also established the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), which brought about the ‘Aadhar’ revolution, an identification number issued to all Indians that became one of the foundations for the country’s mammoth digital payment system that is being hailed by leaders and economists worldwide.

However, fatigue with Singh began to set in, possibly because of the failure of his Pakistan initiative, and possibly because Rahul Gandhi, the scion of the Gandhi family and de-facto Congress party leader, became active through clumsy actions such as publicly shredding a proposed anti-corruption bill.

© Sonu Mehta/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Above all, Singh was the epitome of a quiet and dignified man. US presidents George W Bush and Barack Obama referred to him as scholarly, humble and decent. Former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown called him “incorruptible” and credited him with helping to steer the world through the 2008 economic crisis. Russian President Vladimir Putin hailed the late prime minister’s “significant personal contribution” to bilateral ties. He also called him “an outstanding statesman.”

Manmohan Singh patiently answered even the silliest questions from journalists. He did not write a memoir. He kept quiet when his successor lampooned him Parliament – as he was seated – as if he were wearing a raincoat that shielded his spotless clothes from the corruption in his party. He took his parliamentary duty seriously, even showing up in his wheelchair to vote on a bill on the Delhi government, in August 2023, despite it being a losing cause.

A few months later, his tenure in the Rajya Sabha came to an end, and a few months after that, so did his rich and fulfilling life.