The Battle Of Luzon, Part 4: Victory And Aftermath

The fighting for what remained of a once beautiful and thriving Manila was over by March 1945. Cooperative efforts among U.S. soldiers and civilians to clear away the rubble were underway. On March 13, Sergeant Vincent Powers observed, “The lights are going on all over the city.”

U.S. troops fraternized with Filipinas and traffic jams, many filled with refugees from the fighting still going on, hindered military convoys. But MacArthur refused to deny the natives road access. When asked by an officer why, the General explained: “Look at these people coming towards us…Don’t you get the feeling they’re fleeing something terrible?…Before I interfere with this innocent population, so hard hit by the horrors of war, it will have to be a lot worse for us first.”

As many of those displaced civilians pouring into Manila in search of food and safety could attest, the battle for Luzon was not over. U.S. and Filipino troops pushed towards Yamashita’s main line of resistance holed up in the rugged mountains around Baguio. Supported by the vast network of Philippine guerillas (which included U.S. soldiers who’d managed to avoid captivity in 1942) they marched eastward from Lingayen to retake the summer capital 150 miles north of Manila. During the preliminary air bombardment from March 4 to 10, Kenney’s Fifth Air Force warplanes dropped an estimated 1,185 gallons of napalm and 933 tons of bombs on the city, reducing yet another Philippine town to smoldering rubble.

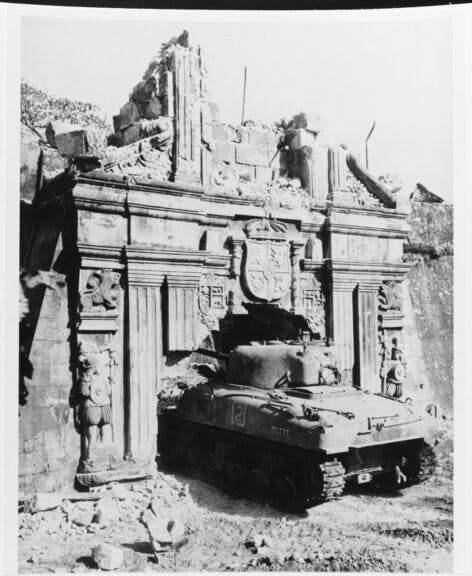

A U.S. Army M-4 “Sherman” tank enters Old Fort Santiago through a somewhat enlarged gate, 26 February 1945. National Archives. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Before the month was over, Yamashita would evacuate Jose Laurel and most of his puppet government officials to Taiwan. The Japanese commander then moved his headquarters to Bombang, 80 miles due east and farther into the Luzon hinterland. A major assault to finally retake Baguio began in mid-April with reinforcements from U.S. troops released from garrison duty in Manila. After heavy fighting, including the final tank battles of the campaign, the last Japanese troops abandoned the city on April 22. Two days later, GIs of the 129th Infantry Regiment entered what remained of the summer capital.

Japanese resistance in the interior of Luzon would continue sporadically until the end of the war. On September 5, 1945, three days following Japan’s formal capitulation on board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Yamashita surrendered the 65,000 starved, wasted remnants of his once formidable 270,000-man command at Baguio’s Camp John Hay. Among those present at the surrender were two gaunt Allied officers who’d just been liberated after years of harsh captivity: U.S. Lt. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, who commanded the doomed Philippine garrison when MacArthur escaped to Australia, and British Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival, who surrendered Singapore and its 80,000 Commonwealth soldiers to Yamashita himself in the dark days of 1942. Interestingly, on March 11, 1974, 2nd Lt. Onda Hiroo, who’d been hiding deep in the jungle, unaware that the war had ended almost three decades earlier, became the last Japanese soldier to surrender on Luzon.

2nd September 1945: Sir Arthur Percival and Jonathan Wainwright salute General Douglas MacArthur (1880 – 1964) as Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces just before he accepts the Japanese unconditional surrender document. On board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Estimated casualties in this largest battle of the Southwest Pacific campaign included roughly 8,400 Army KIA and 30,000 WIA (while another 80,000 were laid low from disease at one time or another). Meanwhile, the Navy suffered another 1,600 dead and 2,100 wounded along with 24 vessels sent to the bottom by suicide attacks. For Japan, as was MacArthur’s hallmark, the butcher’s bill revealed a calamity: over 192,000 KIA with some 10,000 taken prisoner during the actual fighting.

Even as the combat on Luzon raged, U.S. offensives elsewhere were in motion as U.S. Marines stormed Iwo Jima on February 19. Then came the brutal struggle for Okinawa, just 300 miles from Kyushu, starting with the landings on April 1; the walls were closing in on Imperial Japan.

On February 27, 1945, while the battle for Intramuros raged, MacArthur and an entourage that included Philippine Commonwealth President Sergio Osmeña, Romulo, and the General’s Filipino aid Andres Soriano, strode through the red carpeted halls of Malacañang Palace, the Philippine seat of government, which had been spared destruction due to its outlying location. In an impromptu ceremony an emotional MacArthur formally restored the capital to Osmeña. “On behalf of my government, I now solemnly declare, Mr. President, the full power and responsibilities under the constitution restored to the Commonwealth, whose seat is here reestablished as provided by law. Your country, thus, is again at liberty to pursue its destiny to and honored position in the family of free nations.”

The Philippines had been liberated. But it was not the same U.S. protectorate on which the Japanese arrived in 1941. The three-year occupation and months-long reconquest devastated the country. Much of the Philippines’ art treasures and history went up in flames. And its intellectual capital, the doctors, lawyers, engineers, civil servants, businessmen big and small, who’d made the Commonwealth so prosperous and vibrant, had been murdered by the Japanese or died in the fighting. A gaping wound had been torn into the archipelago’s social, cultural, historical, and economic body — from which the islands really never recovered.

JOIN THE MOVEMENT IN ’25 WITH 25% OFF DAILYWIRE+ ANNUAL MEMBERSHIPS WITH CODE DW25

Those Filipinos who escaped Japanese punishment usually fell into two categories: collaborators and guerillas. Collaborators’ motivations varied from survival to outright traitorous opportunism. However, many in the puppet government had been civic and business leaders before the war…and friends to MacArthur. One such example was chameleon-like Manuel Roxas, third in line to the presidency behind the deceased Manuel Quezon and Osmeña. True, Roxas did lead resistance on Mindanao, and after his capture in 1942 he provided intelligence to guerillas throughout the occupation, a capital offense. But he also cooperated with and advised Yamashita, who likely suspected Roxas’ guerilla ties but revealingly spared his life anyway, even as others were executed. Roxas, backed by his family-owned newspapers, would go on to defeat Osmeña in the next election, and on July 23, 1946 become the first President of the globe’s newest nation.

Portrait of Manuel Roxas, President of the Philippines, circa 1946. (Photo by Keystone Features/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Jose Laurel, Tokyo’s puppet President who’d fled to Taiwan, was returned to the Philippines after Japan surrendered. Unlike Roxas, MacArthur had him arrested and imprisoned. In 1948, while Laurel stood trial for 132 counts of treason, President Roxas granted pardons to all collaborators. Laurel was subsequently elected to the Philippine Senate in 1951.

Unlike collaborators, the guerrillas’ motives were more straightforward. And throughout the war, especially as MacArthur’s advances up New Guinea brought him closer to Philippine waters, they provided a steady torrent of invaluable intelligence that both aided the planning of the Philippines Campaign as well as tactics once the forces were on the ground. Their exploits resisting and tormenting their despised occupiers were, in fact, every bit as brave, selfless, and perilous as the more celebrated French Maquis.

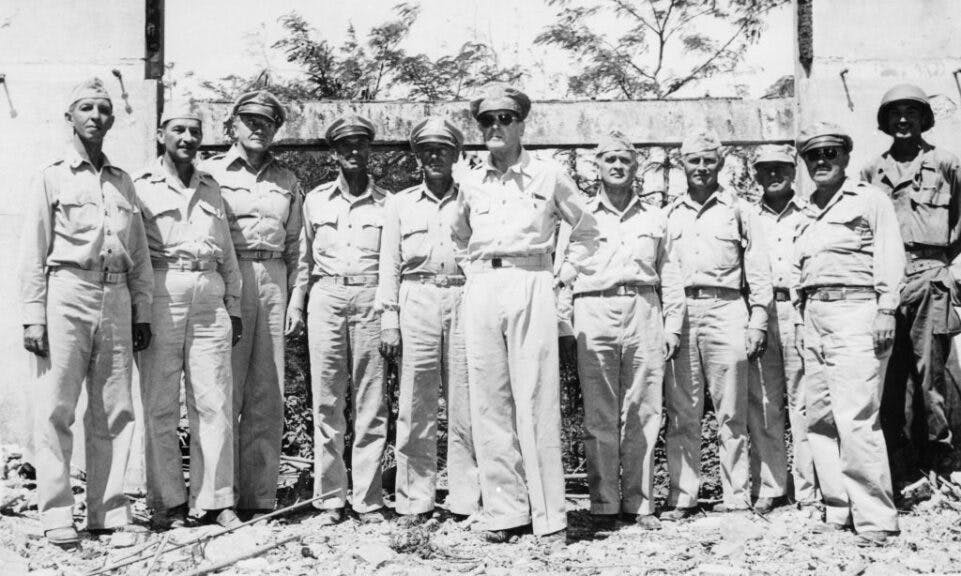

March 1945: American General Douglas MacArthur with members of his staff standing amid the rubble of his former home in the Philippines after fulfilling his promise to return to defeat the Japanese Invaders. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

As for Yamashita, MacArthur showed his former enemy no mercy. Even though evidence offered during a hastily convened, and controversial trial showed Yamashita did not order the massacres in Manila, having left the city himself with the bulk of the Army before they began, the General was unmoved. Certainly Yamashita had been commander during war crimes in Singapore as well as other acts of brutality during the Philippine occupation. But blame for the holocaust that engulfed Manila lay elsewhere. Nevertheless, on February 23, 1946, the angry MacArthur saw the Tiger of Malaya hanged in a dark moment of misplaced retribution.

General Yamashita shortly after capture in Philippines. Jeff Fuglestad Collection. Copyright Owner: Naval History and Heritage Command.

The U.S. had fulfilled its solemn promise to return and liberate those over whom we’d assumed governance from a cruel occupier…even if said promise was unilaterally made by its most celebrated warrior who’d convinced himself his personal declaration upon landing in Australia of “I shall return” bound his entire nation. And as the courage of the Filipinos throughout the occupation and then the fighting amply demonstrated, they returned this loyalty in kind.

But the Philippines paid a terrible price for its freedom. It is estimated that throughout the Second World War, from the Japanese invasion to occupation to Allied reconquest and liberation, over one million Filipinos lost their lives. This was a staggering cost for a populace of just 18 million — a cost that can be argued is still being paid by that troubled yet beautiful and promising island nation to this day.

* * *

At dawn on March 2, 1945, four PT boats chugged up to the rugged shoreline of Corregidor Island. On board were MacArthur, Kenney and other U.S. brass come to formerly declare the island fortress secured. Kenney was amazed at how the land mass had been “smashed beyond recognition,” noting that “even the landscape was altered where the heavy bombs had blown off the tops of hills.”

The vessels docked and MacArthur climbed the ladder onto the pier. He was greeted by Col. George M. Jones, commander of the “Rock Force”, made up of the 503rd Parachute Regimental Combat Team and the 3rd battalion, 34th U.S. Infantry, who retook the island. The colonel saluted crisply and said, “Sir, I present to you fortress Corregidor.”

MacArthur first awarded Jones the Distinguished Service Cross. Then, in a determined voice The General said: “I see that the old flagpole still stands. Have your troops hoist the colors to its peak, and let no enemy ever haul them down.”

Parachutes discarded by airborne troops still hang from the tree tops as the US flag is raised over Corregidor following the island’s recapture, Philippines, March 2nd 1945. General MacArthur stands to the left of the flagpole, saluting as the colours are hoisted. (Photo by Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

* * *

RELATED: The Battle Of Luzon, Part 1: Climax Of The Southwest Pacific War

RELATED: The Battle Of Luzon, Part 2: Race To Manila

RELATED: The Battle Of Luzon, Part 3: The Massacre Of Manila

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities fund manager, author, and columnist whose articles have appeared on the pages of The Daily Wire, The Wall Street Journal, NY Post, NY Daily News, National Review, The Hill, The Federalist, Zerohedge, and other outlets. He is the author of three books. Follow him on Substack and X/Twitter.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.