The Dreyfus Affair: A Shameful Manifestation Of Anti-Semitism In France

The following is an excerpt from the new book “The Battle For The Jewish State: How Israel — And America — Can Win,” by Victoria Coates (December 17, 2024, Encounter Books).

* * *

The Dreyfus Affair

While the Holocaust executed by Nazi Germany may be the most sensational example of antisemitism in Europe, hatred of Jews has been a perennial and insidious evil on the Continent since antiquity, gaining strength through the medieval period and persisting into our own time. Despised as an “inferior race,” the Jews became Europe’s routine outsider scapegoats. One of the most infamous instances of such scapegoating, the Dreyfus Affair in late-nineteenth-century France, was a harbinger of horrors to come—horrors that would necessitate the establishment of a Jewish state that would, in time, become a critical ally to the United States.

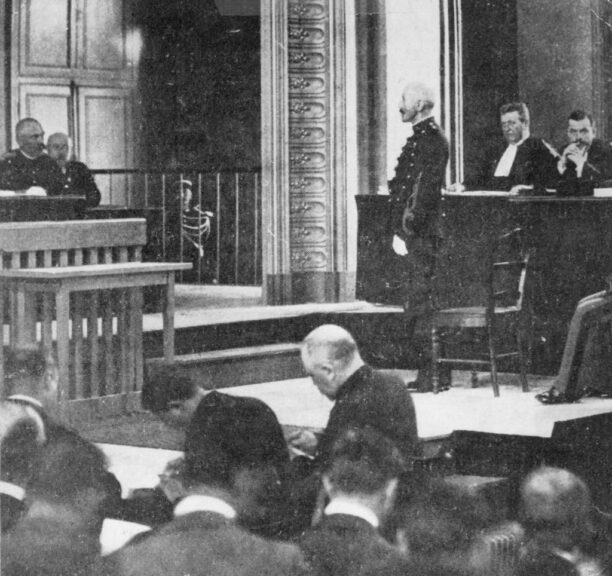

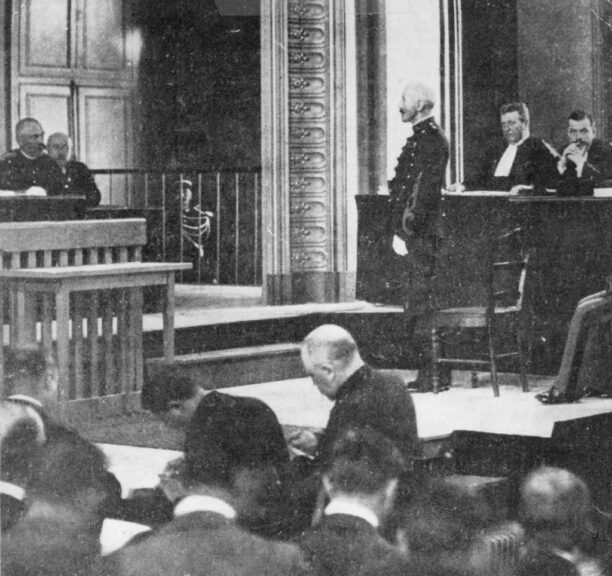

During the Third Republic, Alfred Dreyfus, a young Jewish army officer, was accused of selling military secrets to the Germans, including cutting-edge French weapon designs.(1) A document allegedly in Dreyfus’s handwriting seemed to prove his guilt, and in January 1895 he was convicted of treason by a closed court martial. In a humiliating ceremony formally expelling him from the French army, Dreyfus’s medals and insignia of rank were torn from his uniform and his sword broken, and he was paraded in front of the assembled officers, who jeered him as a traitor and a Jew. He was shipped off to Devil’s Island, the notorious penal colony off the coast of French Guiana, where the mortality rate was so high that it was known as the “dry guillotine.”

Alfred Dreyfus, an artillery captain in the French Army accused of anonymously sending secret documents to the German embassy in Paris, is tried for treason before a court-martial at Rennes. (Photo by Henry Guttmann Collection/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

That should have been the end of Dreyfus, but the lack of substantial evidence remained troubling to some observers, as did the growing impression that he had been targeted primarily because he was a Jew. Eventually it was revealed that it would have been logistically impossible for Dreyfus to have had dealings with the Germans in question. Another suspect emerged, one whose handwriting more closely matched the incriminating document than Dreyfus’s. The case that had once seemed open and shut began to look like a set-up.

The Dreyfus Affair was hotly debated between the traditionalists, who saw the controversy as a Jewish plot to undermine traditional French military culture, and progressives, who believed the persecution of Dreyfus was a shameful manifestation of antisemitism masked by the anti-German sentiment of that period following the Franco-Prussian War. The new French President Félix Faure, who had inherited the scandal, became the de facto leader of the traditionalists, while the journalist and future prime minister Georges Clemenceau spearheaded the effort to clear Dreyfus.

On January 13, 1898, the front page of Clemenceau’s newspaper L’Aurore screamed “J’Accuse … !” Distilling the concerns and misgivings about the Dreyfus Affair into one resonant phrase, the headline introduced an open letter to President Faure by the critic and author Émile Zola. It was the most detailed account of the injustices done to Dreyfus and a warning to the president that the scandal threatened to engulf his administration. Acknowledging that his letter potentially violated the law as libel, Zola defiantly declared, “My fiery protest is the cry of my very soul.”(2)

Zola was duly convicted of libel and fled to England, but the case against Dreyfus began to fall apart. A second court martial convicted him again but commuted his sentence, and ten days later he was pardoned by a new president. Acceptance of the pardon required an admission of guilt, but Dreyfus was fully exonerated in 1906.

While justice had finally been done for Dreyfus, Jews sensed a growing threat. Many believed that they could no longer depend on assimilating into European culture, as had been the hope, but needed to establish their own state to protect themselves. The Dreyfus Affair inspired the pioneering Zionist Theodor Herzl to write The Jewish State: An Attempt at a Modern Solution to the Jewish Problem in 1896, laying out the case for reestablishing a Jewish nation in the Holy Land.

The concept was hardly new, as Jews had been living in the region for millennia and had governed it as far back as the time of King David. But for the Austro-Hungarian Herzl, the pogroms of isolation and marginalization of the nineteenth century made the project immediate and urgent. As a young man he had hoped that enlightenment would lead to the end of antisemitism. However, he came to believe that hatred of Jews in Europe was so entrenched that the only real solution was a state for Jews in their ancestral homeland, where they could live and worship in peace and security. Herzl pressed his case with everyone from the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II to Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany. The organizations that would eventually provide the foundation of the Israeli government, notably the Zionist Congress and the Jewish Agency, were formed.

Herzl’s proposition was controversial, but it was also powerful, and modern Zionism gained steam after his death in 1904. Had his vision of a safe haven for Jews been realized in the early twentieth century, one of the greatest evils in history might have been avoided. But it was not yet to be. The gathering antisemitism he identified in European society spread into the mainstream in Germany in the 1920s, feeding on the general discontent following Germany’s humiliating loss in World War I.

* * *

CHECK OUT THE DAILY WIRE HOLIDAY GIFT GUIDE

* * *

Victoria Coates is the Vice President of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy at The Heritage Foundation. Coates previously served as the Senior Policy Advisor to the Secretary of Energy and Deputy National Security Advisor for the Middle East and North Africa on the NSC, both for President Donald J. Trump, as well as the National Security Advisor for Senator Ted Cruz. Coates holds a B.A. from Trinity College, a M.A. from Williams College, and a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania, all in art history.

This excerpt is published by permission from Encounter Books. “The Battle For The Jewish State: How Israel — And America — Can Win,” by Victoria Coates (December 17, 2024, Encounter Books). © 2024 by The Heritage Foundation Foreword © 2024 Ted Cruz.

The views expressed in this book excerpt do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

* * *

NOTES:

CHAPTER TWO: WHY ISRAEL? AMERICA AND THE JEWISH STATE

- Victoria C. Gardner Coates, David’s Sling: A History of Democracy in Ten Works of Art (New York: Encounter Books, 2016), 240–42.

- Émile Zola, “J’Accuse . . . !,” L’Aurore, January 13, 1898.